Review

If there are two books that any tech product manager should have read at the very beginning of his career, then it is “Crossing the chasm” from Geoffrey A. Moore and “The innovator’s dilemma” from Clayton M. Christensen. The first learns you how to walk through the product lifecycle and the second will warn you to be vigilant about market disruptors at any time while growing up. While both works have respectable age (“Crossing the chasm” had its first edition in 1991 and ” The innovator’s dilemma” appeared in 1997), they are still very valid today and I would advise every product manager or marketeer to read them if you haven’t done so yet.

The product lifecycle that is described in this book applies to almost any tech product. One of the first things I have always done when I started in a new company or project was to get a historical overview of the sales numbers and process them in an Excel graph. Believe it or not but I have encountered this graph on every occasion. The only differentiator was the speed with which the graph climbed and the heigh of it. Some products come and fade in 18 months; others last for many years; this is a characteristic of the business you are in. It is of uttermost importance for every product manager to know where exactly you are in this curve in order to plan ahead for the next curve. If the sales numbers of a new product get stuck, you may be at the ‘chasm’ level of the graph and special measures should be taken to jump into the mass sales part – this book will learn you how.

One of the most important concepts in this book is the “whole product”. A product is to be considered in its context as a solution to a problem and includes much more than just the physical item or some piece of software. Documentation, training, interoperability, packaging, … every single detail that is related to the product contributes to the buyer experience and his impression about the product.

The solution to cross the chasm according to Moore is to target a specific application with limited specs, a geographic area or maybe a specific system integrator’s environment that is strategic to conquer the rest of the market. This is indeed a much more sensible approach than designing a product that tries to do it all from the beginning on. The term minimum viable product applies very much in this context.

If there is one remark to make about the book, it is the same remark as for many renowned business books: this is a US-born ‘Harvard-business-school’-style of management book and you can’t just blindly project every lesson to the average European or Asian company. First, there is a difference in size: most of us don’t work for the HPs, Microsofts or Googles in this world but for much smaller organizations. Second, there is a difference in culture: we do not all live the American dream and some have other ambitions besides being the world leader. This reflects also in the market size: only a handful of countries in the world have a vast area of several thousand km² with hundreds of millions of habitants that share more or less a single language, a single authority and a single monetary unit, as the US has. Most of us have to deal with limited markets and need to translate and deal with cultural differences and exchange rates as soon as we leave the border, only a few hundreds of km away from us. Therefore, do not blindly adapt US management books without using common sense and adapting it to your own environment. It still is an extremely important lesson, but use with care!

Summary

Part 1: Discovering the chasm

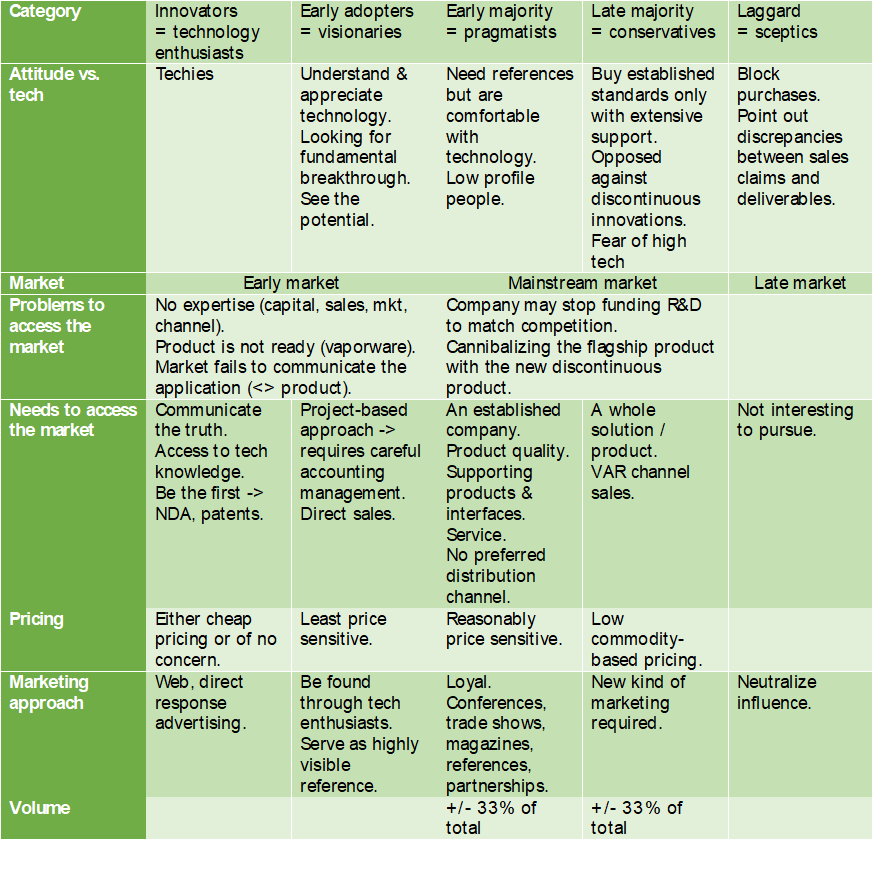

In this part, Moore explores the technology adoption curve as was popularized by the book ” Diffusion of Innovations” by Everett Rogers in 1962. It portraits the different phases that a technology goes through as it grows and eventually disappears again in the market. The curve applies to discontinuous innovations – that are products that change our behaviour. It does not apply to continuous innovations, more like upgrades of products. The curve applies to a market, defined as a set of actual or potential customers for a given set of products or services who have a common set of needs or wants and who reference each other when making a buying decision.

The curve is characterized by 5 different categories of buyers in 3 different market categories with different attitudes towards technology, specific problems &, needs that arise, a different pricing sensitivity and different purchase channels.

The essence of a high-tech marketing model should walk this curve from left to right during a limited time, matching the window of opportunity. However, Moore indicates a discontinuity in the curve, calling it ‘the chasm’ where one moves into a highly reference- and support-oriented audience without having solid references and an establish support base. It is about convincing pragmatics, who differ from visionaries. Visionaries

- Have less or no respect for the value of colleagues’ experiences.

- Take greater interest in technology than average in their industry.

- Fail to recognize the importance of existing product infrastructure.

- Adhere to a disruptive nature.

A market is defined as a set of actual or potential customers for a given set of products or services who have a common set of needs or wants and who reference each other when making a buying decision.

Part 2: Crossing the chasm

Crossing the chasm requires to overcome some difficulties:

- Lack of new customers from the early market.

- Competition is wakening.

- Management wants to rely on existing major account relationships.

- Investors expect an early return on investment or even discredit current management for not succeeding.

The advised strategy to overcome these difficulties is to win entry into the mainstream market by targeting a very specific niche market that is strategic – meaning it creates an entry into larger segments.

To do so, the company may not be sales driven since:

- The ‘whole product’ ( = product including all related assets such as packaging, documentation, marketing collateral, etc.) is not ready yet.

- A word-to-mouth reputation does not exist yet.

- We need to achieve market leadership first.

Moore describes this process poetically in analogy with the D-day invasion in Normandy: targeting the point of attack assembling the invasion force, defining the battle and finally launching the invasion.

2.1. Target the point of attack

Choosing the niche market to focus on first is a high-risk, low-data decision. Numeric info is based on existing markets, thus maybe limited validity. Still, information intuition rather than analytical data is a trustworthy decision tool.

Characterize and validate the niche customer segment through these steps:

- Define the customer problem(s).

- Describe & quote showstoppers for each scenario (1-4 = high importance, 5-9 = nice to have):

- Does target customer have sufficient funding and is he accessible?

- What are compelling reasons to buy: is the problem big enough to pay for? (Willingness to pay)

- Consider the whole product / solution: can we (& partners) provide a complete solution?

- Competition: does a solution exists already?

- Partners & allies: existing or do we need new ones?

- Distribution: do we have knowledge on accessing the niche?

- Pricing: is our price consistent with customer budget? Consider additional channel reward.

- Positioning: our credibility.

- How to access next target customer segment from here = ‘bowling pin’ potential?

- Limit this exercise to 1 segment only! If the segment does not fit or is not agreed upon, stop the attempt and find another.

- Commit to the choice and validate it with early market research.

The target segment should deliver approximately 50% of projected yearly sales of the new product.

2.2. Assemble the invasion force

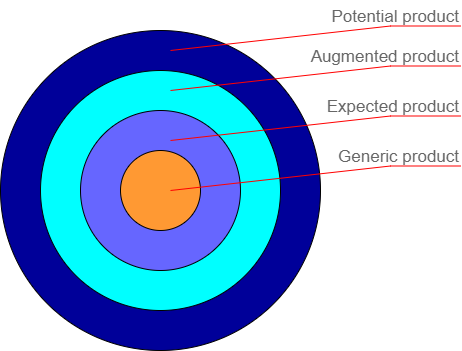

For this phase, Moore refers to the concept of whole product as introduced by Theodore Levitt “The marketing Imagination”. This indicates a difference between what the marketing promises, the compelling value proposition and what the product actually fulfils.

To close that gap, we should consider the different levels of ‘the whole product’:

- The generic product = the product as shipped

- The expected product = what the customer expected to receive = the minimum feature set that covers the buyers objective

- The augmented product = the configuration with maximum chance to cover the customers expectation

- The potential product = opportunities for growth

Pragmatists are buying and evaluating the “whole product”. So to attack the market, we define additional hardware & software, provide system integration, installation & debugging support training and comply to standards and procedures, etc. Select the minimum set to enter the market. Define what to do ourselves and for which partners are needed.

Note that Partnerships & strategic alliances tend to fail due to different cultures, decision cycles etc. Tactical alliances should only have one purpose: accelerate the formation of a whole product infrastructure within a specific market segment.

2.3. Define the battle

Pragmatists require competition = comparative evaluation of products & vendors within a common category. Create / choose credible competition.

The competitive compass positions buyer interest in – and understanding of technology (horizontal axis) vs. the buyer attitude towards value proposition (vertical axis). Even the most sceptical specialists are looking for new technology. Even sceptical generalists are interested in new market development. But crossing the chasm is an unnatural market rhythm.

We should look for market-centric competition (as opposed to product-centric): solutions with a large install base, third-party support, complying to standards, having a low cost of ownership and adequate support.

Positioning the product in this competitive environment requires to create an easy-to-buy space. It is about product association. Find the single largest influence on the buying decision; people are conservative about changing the positioning.

Work the 4 stages of positioning:

- Name and frame it: define a clear category for technology enthusiasts.

- Clarify the who and what for the visionaries

- Work on differentiation to competition for the pragmatists

- Elaborate on the financials and future evolution for conservatives.

This translates in 4 actions:

- Claim market leadership in the target market. Do the elevator test: a simple wording of the product strength:

For … (target customer),

who are dissatisfied with … (current market alternative),

our product is a … (category)

that provides … (problem solution)

unlike … (product alternative),

we have assembled … (whole product). - Measure the evidence. For pragmatist, this is market share. In lack of market share: partner quantity & quality & their commitment

- Communications to the right audiences in the right sequence. Do a whole product launch in related business press.

- Assemble feedback and adjust related to competition. This is a dynamic process.

2.4. Launch the invasion

Set criteria for distributors:

- Distinguish demand creators from demand fulfillers.

- What role do distributors play in the whole product?

- What is the potential for high volumes?

Different types of distribution channels:

- Direct sales is optimal for creating demand at high prices (>75 K€). It requires an uncompetitive agenda and is based on relationships. This is the best channel for crossing the chasm.

- (Two-tier retail)

- One-tier retail (= superstores): these fulfil demand. This channel is structurally unsuited for crossing the chasm but ok once market is established. An intermediate step is possible: direct response adds, telesales, VAR. Suited for prices < 10K$.

- Internet retail: no need for support. Unsuited for chasm.

- VAR: products too complex for retail. Problems here are lack of marketing, a shortage of qualifiable VAR’s and they stop selling when targets are reached.

- OEM: have no patience for special demands of chasm product.

- System integrators: project-oriented, typical government market. Important for design decisions and supplier relationships!

Selling partnerships are ok for short term only.

How to set price?

- Customer-oriented pricing:

- Visionaries: value based.

- Conservatives: cost based.

- Vendor-oriented pricing: cost of sales, goods, … = worst practice for chasm crossing.

- Distribution –oriented pricing: high enough to claim market leadership with disproportional high reward for the channel, to be phased out as the product gets established

Part 3: beyond the chasm

Be aware that the post-chasm enterprise is bound to commitments of the pre-chasm period.

Revenues will typically staircase, rather than hockey-stick graph.

A number of organizational decisions are due: financing, R&D role shift, sales shift, operate as a whole product manager.

More information on market strategy and product management methods can be found in my book “Practical Product Management”. Go to https://www.neobasics.be/product/shop-practical-product-management for a description of the book contents, a preview and how to order it.

Leave a Reply